“Of the music of the universe, some is characteristic of the elements, some of the planets, some of the season: of the elements in their mass, number, and volume; of the planets in their situation, motion, and nature; of the season in days (in the alternation of day and night), in months (in the waxing and waning of the moons), and in years (in the succession of spring, summer, autumn, and winter).”

Hugh of St. Victor

Monday, December 21, 2009

Music and Harmonia

“For all that we might smile benignly at in the mathematical clumsiness and rhetorical hyperbole of the classical philosopher of music or in the intellectual abstractions and tetchy fussiness of the medieval theorist, is there not something in the notion of being ‘cradles’ in God’s created harmonia that is worth recovering?”

Jeremy Begbie, Resounding Truth: Christian Wisdom in the World of Music

Jeremy Begbie, Resounding Truth: Christian Wisdom in the World of Music

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Facts and Truth

Because we come from a common origin, there’s a desire for that which is true. Myth is more powerful as a weapon for cultural renewal than math and science. When you want facts, look in an encyclopedia. When you want truth, look in songs, art, literature, and sculpture. In our rationalistic way, we think facts are truth, but facts and truth are not the same. Our desire to make them the same is why we sometimes never move on from knowledge into wisdom.

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Chesterton on Myth

“Mythology is a search. It combines a recurrent desire with a recurrent doubt. It’s not the prophet saying, ‘These things are.’ It’s the voice of a dreamer saying, ‘Why cannot these things be?’”

—G. K Chesterton

—G. K Chesterton

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Longing for Beauty

The books or music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them: it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself, they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of the worshipers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news form a country we have never yet visited.

—C.S. Lewis

—C.S. Lewis

Monday, November 2, 2009

Beauty

“We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance.”

When beauty is lost, “the whole of worldly being falls under the dominion of ‘knowledge.’ And the springs and forces of love immanent in the world are overpowered and finally suffocated by science, technology and cybernetics. The result is a world without women, without children, without reverence for love…a world in which power and the profit-margin are the sole criteria, where the disinterested, the useless, the purposeless is despised, persecuted and in the end exterminated—a world in which art itself is forced to wear the mask and features of technique.”

—Hans Urs van Balthasar

When beauty is lost, “the whole of worldly being falls under the dominion of ‘knowledge.’ And the springs and forces of love immanent in the world are overpowered and finally suffocated by science, technology and cybernetics. The result is a world without women, without children, without reverence for love…a world in which power and the profit-margin are the sole criteria, where the disinterested, the useless, the purposeless is despised, persecuted and in the end exterminated—a world in which art itself is forced to wear the mask and features of technique.”

—Hans Urs van Balthasar

Legends, Fairy Tales and Truth

“All too often the legends old men tell are closer to the truth than the facts young professors tell. The wildest fairy tales of the ancients are far more realistic than the scientific phantasms imagined by moderns.” —Hilaire Belloc

Thursday, July 23, 2009

Symbolism Book List

Following is the books list I'll be using this year to teach the inaugural course on Symbolism at our new college.

Dictionary of Biblical Imagery General Editors: Leland Ryken, James C. Wilhoit & Tremper Longman III

On Christian Teaching by Augustine (selections)

Cratylus by Plato

Signs and Mysteries Revealing Ancient Christian Symbols by Mike Aquilina

Genesis

Through New Eyes by James Jordan

The Elizabethan World Picture by E. M. W. Tillyard

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C. S. Lewis

Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants and Trees by Ernst and Johanna Lehner

Dictionary of Symbolism by Hans Beidermann

The Book of Beasts by T.H. White

The Theology of Arithmetic translated by Robin Waterfield

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by JK Rowling

War in Heaven by Charles Williams

Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves by Edmund Spenser, ed Roy Maynard

Pieter Bruegel: 1525/30-1569 (masters of Netherlandish Art) by HF Ullman

Alchemy: The Great Secret by Andrea Aromatico

Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition by Michel Pastoureau

Shakespeare, Donne, Herbert Poems

Dictionary of Biblical Imagery General Editors: Leland Ryken, James C. Wilhoit & Tremper Longman III

On Christian Teaching by Augustine (selections)

Cratylus by Plato

Signs and Mysteries Revealing Ancient Christian Symbols by Mike Aquilina

Genesis

Through New Eyes by James Jordan

The Elizabethan World Picture by E. M. W. Tillyard

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C. S. Lewis

Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants and Trees by Ernst and Johanna Lehner

Dictionary of Symbolism by Hans Beidermann

The Book of Beasts by T.H. White

The Theology of Arithmetic translated by Robin Waterfield

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by JK Rowling

War in Heaven by Charles Williams

Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves by Edmund Spenser, ed Roy Maynard

Pieter Bruegel: 1525/30-1569 (masters of Netherlandish Art) by HF Ullman

Alchemy: The Great Secret by Andrea Aromatico

Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition by Michel Pastoureau

Shakespeare, Donne, Herbert Poems

Labels:

Alchemy,

Colors,

Cosmology,

Dragons,

Four Elements,

Heraldry,

Labyrinths,

Lilith,

Numbers,

Theology

Monday, May 4, 2009

Song of Creation

This following is from Spurgeon's Cheque Book of the Bank of Faith from May 1:

The mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. (Isaiah 55:12)

When sin is pardoned, our greatest sorrow is ended, and our truest pleasure begins. Such is the joy which the Lord bestows upon His reconciled ones, that it overflows and fills all nature with delight. The material world has latent music in it, and a renewed heart knows how to bring it out and make it vocal. Creation is the organ, and a gracious man finds out its keys, lays his hand thereon, and wakes the whole system of the universe to the harmony of praise. Mountains and hills, and other great objects, are, as it were, the bass of the chorus; while the trees of the wood, and all things that have life, take up the air of the melodious song.

When God's Word is made to prosper among us and souls are saved, then everything seems full of song. When we hear the confessions of young believers and the testimonies of well-instructed saints, we are made so happy that we must praise the Lord, and then it seems as if rocks and hills and woods and fields echo our joy-notes and turn the world into an orchestra. Lord, on this happy May Day, lead me out into thy tuneful world as rich in praise as a lark in full song.

The mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. (Isaiah 55:12)

When sin is pardoned, our greatest sorrow is ended, and our truest pleasure begins. Such is the joy which the Lord bestows upon His reconciled ones, that it overflows and fills all nature with delight. The material world has latent music in it, and a renewed heart knows how to bring it out and make it vocal. Creation is the organ, and a gracious man finds out its keys, lays his hand thereon, and wakes the whole system of the universe to the harmony of praise. Mountains and hills, and other great objects, are, as it were, the bass of the chorus; while the trees of the wood, and all things that have life, take up the air of the melodious song.

When God's Word is made to prosper among us and souls are saved, then everything seems full of song. When we hear the confessions of young believers and the testimonies of well-instructed saints, we are made so happy that we must praise the Lord, and then it seems as if rocks and hills and woods and fields echo our joy-notes and turn the world into an orchestra. Lord, on this happy May Day, lead me out into thy tuneful world as rich in praise as a lark in full song.

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Chesterton and Labyrinths

"What we all dread most is a maze with no centre. That is why atheism is only a nightmare."

--G.K. Chesterton, Father Brown Mystery, The Head of Caesar

--G.K. Chesterton, Father Brown Mystery, The Head of Caesar

Sunday, March 29, 2009

Cosmological Harmony

Cosmological harmony was actually one of the few ideas on which philosopher, scientists, and theologians of Bach’s time were agreed. Newton, for example, could not imagine that a world so orderly as this one could have occurred by “natural Cause alone.” A “powerful, ever-living Agent…governs all things,” he concluded, “not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all.”

—James R. Gaines, Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment

—James R. Gaines, Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Children and Fairy Stories

It is accused of giving children a false impression of the world they live in. But I think no literature that children could read gives them less of a false impression. I think what profess to be realistic stories for children are far more likely to deceive them. I never expected the real world to be like the fairy tales. I think that I did expect school to be like the school stories. The fantasies did not deceive me: the school stories did. All stories in which children have adventures and successes which are possible, in the sense that they do not break the laws of nature, but almost infinitely improbable, are in more danger than the fairy tales of raising false expectations.

Almost the same answer serves for the popular charge of escapism, though here the question is not so simple.

Do fairy tales teach children to retreat into a world of wish-fulfillment— 'fantasy' in the technical psychological sense of the word— instead of facing the problems of the real world? Now it is here that the problem becomes subtle…The other longing, that for fairy land, is very different. In a sense a child does not long for fairy land as a boy longs to be the hero of the first eleven. Does anyone suppose that he really and prosaically longs for all the dangers and discomforts of a fairy tale?—really wants dragons in contemporary England? It is not so. It would be much truer to say that fairy land arouses a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his life-long enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted. This is a special kind of longing. The boy reading the school story of the type I have in mind desires success and is unhappy (once the book is over) because he can't get it: the boy reading the fairy tale desires and is happy in the very fact of desiring. For his mind has not been concentrated on himself, as it often is in the more realistic story.

…For, as I say, there are two kinds of longing. The one is an askesis, a spiritual exercise, and the other is a disease.

A far more serious attack on the fairy tale as children's literature comes from those who do not wish children to be frightened…Those who say that children must not be frightened may mean two things. They may mean (1) that we must not do anything likely to give the child those haunting, disabling, pathological fears against which ordinary courage is helpless: in fact, phobias. His mind must, if possible, be kept clear of things he can't bear to think of. Or they may mean (2) that we must try to keep out of his mind the knowledge that he is born into a world of death, violence, wounds, adventure, heroism and cowardice, good and evil. If they mean the first I agree with them: but not if they mean the second. The second would indeed be to give children a false impression and feed them on escapism in the bad sense. There is something ludicrous in the idea of so educating a generation which is born to the Ogpu and the atomic bomb. Since it is so likely that they will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. Otherwise you are making their destiny not brighter but darker. Nor do most of us find that violence and bloodshed, in a story, produce any haunting dread in the minds of children. As far as that goes, I side impenitently with the human race against the modern reformer. Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons, giants and dragons, and let villains be soundly killed at the end of the book. Nothing will persuade me that this causes an ordinary child any kind or degree of fear beyond what it wants, and needs, to feel. For, of course, it wants to be a little frightened.

The other fears—the phobias—are a different matter. I do not believe one can control them by literary means…And I think it possible that by confining your child to blameless stories of child life in which nothing at all alarming ever happens, you would fail to banish the terrors, and would succeed in banishing all that can ennoble them or make them endurable. For in the fairy tales, side by side with the terrible figures, we find the immemorial comforters and protectors, the radiant ones; and the terrible figures are not merely terrible, but sublime. It would be nice if no little boy in bed, hearing, or thinking he hears, a sound, were ever at all frightened. But if he is going to be frightened, I think it better that he should think of giants and dragons than merely of burglars. And I think St George, or any bright champion in armor, is a better comfort than the idea of the police.

—C.S. Lewis, On Three Ways of Writing for Children

Almost the same answer serves for the popular charge of escapism, though here the question is not so simple.

Do fairy tales teach children to retreat into a world of wish-fulfillment— 'fantasy' in the technical psychological sense of the word— instead of facing the problems of the real world? Now it is here that the problem becomes subtle…The other longing, that for fairy land, is very different. In a sense a child does not long for fairy land as a boy longs to be the hero of the first eleven. Does anyone suppose that he really and prosaically longs for all the dangers and discomforts of a fairy tale?—really wants dragons in contemporary England? It is not so. It would be much truer to say that fairy land arouses a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his life-long enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted. This is a special kind of longing. The boy reading the school story of the type I have in mind desires success and is unhappy (once the book is over) because he can't get it: the boy reading the fairy tale desires and is happy in the very fact of desiring. For his mind has not been concentrated on himself, as it often is in the more realistic story.

…For, as I say, there are two kinds of longing. The one is an askesis, a spiritual exercise, and the other is a disease.

A far more serious attack on the fairy tale as children's literature comes from those who do not wish children to be frightened…Those who say that children must not be frightened may mean two things. They may mean (1) that we must not do anything likely to give the child those haunting, disabling, pathological fears against which ordinary courage is helpless: in fact, phobias. His mind must, if possible, be kept clear of things he can't bear to think of. Or they may mean (2) that we must try to keep out of his mind the knowledge that he is born into a world of death, violence, wounds, adventure, heroism and cowardice, good and evil. If they mean the first I agree with them: but not if they mean the second. The second would indeed be to give children a false impression and feed them on escapism in the bad sense. There is something ludicrous in the idea of so educating a generation which is born to the Ogpu and the atomic bomb. Since it is so likely that they will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. Otherwise you are making their destiny not brighter but darker. Nor do most of us find that violence and bloodshed, in a story, produce any haunting dread in the minds of children. As far as that goes, I side impenitently with the human race against the modern reformer. Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons, giants and dragons, and let villains be soundly killed at the end of the book. Nothing will persuade me that this causes an ordinary child any kind or degree of fear beyond what it wants, and needs, to feel. For, of course, it wants to be a little frightened.

The other fears—the phobias—are a different matter. I do not believe one can control them by literary means…And I think it possible that by confining your child to blameless stories of child life in which nothing at all alarming ever happens, you would fail to banish the terrors, and would succeed in banishing all that can ennoble them or make them endurable. For in the fairy tales, side by side with the terrible figures, we find the immemorial comforters and protectors, the radiant ones; and the terrible figures are not merely terrible, but sublime. It would be nice if no little boy in bed, hearing, or thinking he hears, a sound, were ever at all frightened. But if he is going to be frightened, I think it better that he should think of giants and dragons than merely of burglars. And I think St George, or any bright champion in armor, is a better comfort than the idea of the police.

—C.S. Lewis, On Three Ways of Writing for Children

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Musical Counterpoint and the Cosmos

The constant motion of the heavens is thus analogous to the perpetual revolution of the parts in a well-constructed piece of double counterpoint, whose inversions mirror the perfection of heaven and provide earthly beings with a glimpse of God’s unending order, a prelude to the heavenly concert.

But the relationship between these phenomena was more than simply one of likeness: the mechanics of the heavens were not simply allegorized by double counterpoint, they were manifested in its workings.

—David Yearsley, Bach and the Meanings of Counterpoint

But the relationship between these phenomena was more than simply one of likeness: the mechanics of the heavens were not simply allegorized by double counterpoint, they were manifested in its workings.

—David Yearsley, Bach and the Meanings of Counterpoint

Music and the Four Elements

Let me note first that musicians most often write for four parts, which, they find, contain the full perfection of harmony. Therefore they call these parts elemental after the four elements. As every physical body is composed of the elements, so every perfect composition is composed of the elemental parts. The lowest voice part is called the bass; it is analogous to the element of earth, which I slowest of the elements. The next part in ascending order is the tenor, which is analogous to water. It is just above the earth and united to it; similarly the tenor immediately follows the bass, and its low tones are indistinguishable from the high tones of the bass. The next voice part above the tenor is called by some the contratenor, by others the contralto or alto. Its position, third and central among the voices, is analogous to that of air; as air blends in a certain way with water and fire, so the low alto tones blend with the high tenor tones, while the high alto tones blend with the low tones of the fourth and highest voice, the canto. This voice, called by some the soprano because of its supreme position, is analogous to fire, which follows air and holds the highest place.

—Gioseffo Zarlino, The Art of Counterpoint: Part Three of Le Istitutioni harmoniche, 1558

—Gioseffo Zarlino, The Art of Counterpoint: Part Three of Le Istitutioni harmoniche, 1558

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

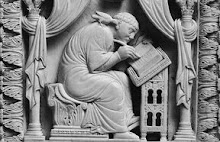

Architecture and Belief

Church architecture affects the way man worships; the way he worships affects what he believes; and what he believes affects not only his personal relationship with God but how he conducts himself in his daily life…

One basic tenet that architects have accepted for millennia is that the built environment has the capacity to affect the human person deeply—the way he acts, the way he feels, and the way he is. Church architects of past and present understood that the atmosphere created by the church building affects not only how we worship, but also what we believe. Ultimately, what we believe affects how we live our lives. It’s difficult to separate theology and ecclesiology from the environment for worship, whether it's a traditional church or a modern church.

—Michael S. Rose, Ugly as Sin

One basic tenet that architects have accepted for millennia is that the built environment has the capacity to affect the human person deeply—the way he acts, the way he feels, and the way he is. Church architects of past and present understood that the atmosphere created by the church building affects not only how we worship, but also what we believe. Ultimately, what we believe affects how we live our lives. It’s difficult to separate theology and ecclesiology from the environment for worship, whether it's a traditional church or a modern church.

—Michael S. Rose, Ugly as Sin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)